From Clickbait to Credibility: A Guide to Smarter Information Choices

Science literacy includes:

- Gathering information from reliable sources

- Accurately interpreting scientific research

- Recognizing misinformation

- Engaging in productive scientific discussions

- Making well-informed decisions that impact you as well as your community

Cultivating science literacy allows you to stay informed, engaged and unbiased as you navigate the overload of information and any misinformation traps.

This post will focus on helpful tips for finding and evaluating reliable sources and spotting red flags for misinformation.

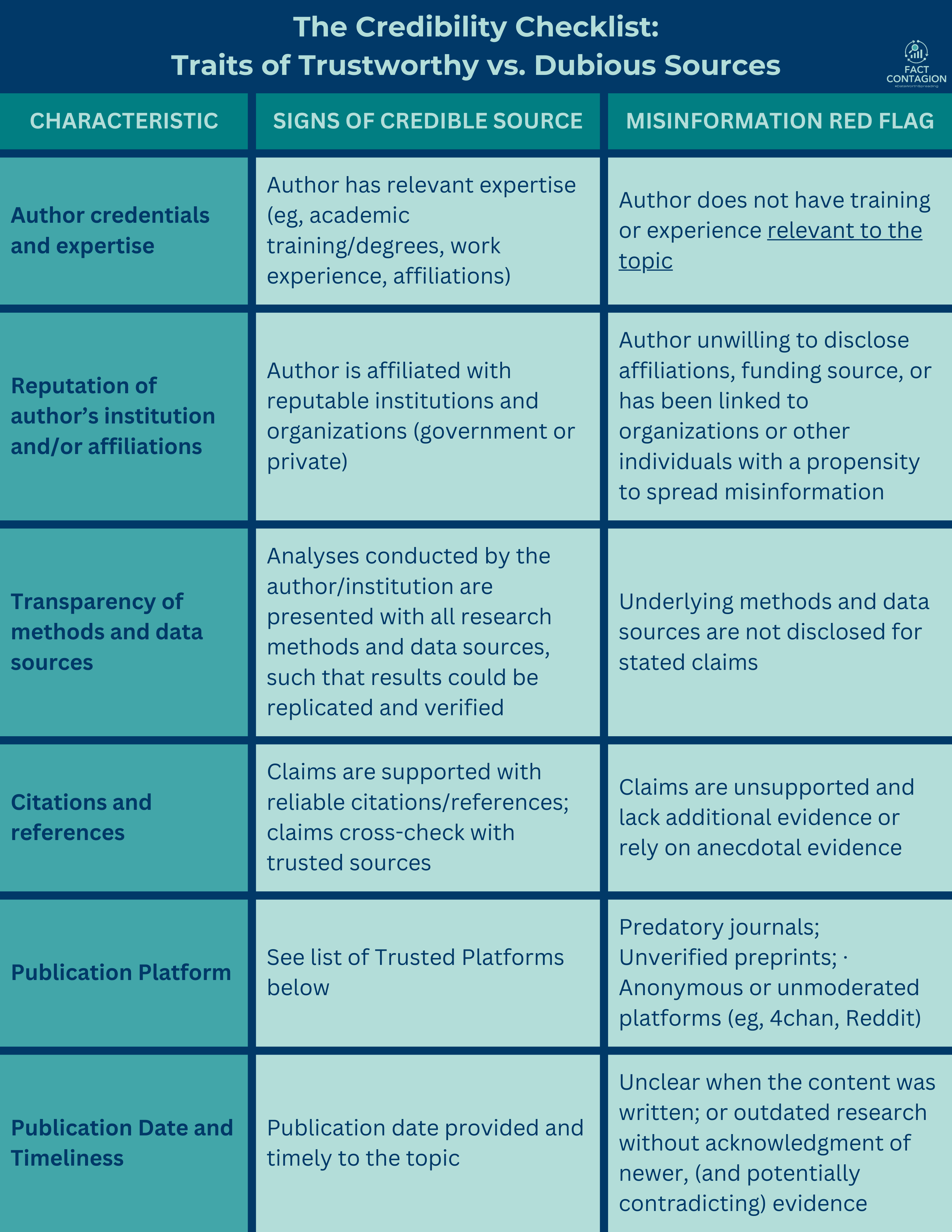

What Makes a Source Credible?

There are several characteristics to consider when evaluating the reliability of a source. The table below describes what to look for in a trusted source, versus potential red flags that warrant caution or further investigation.

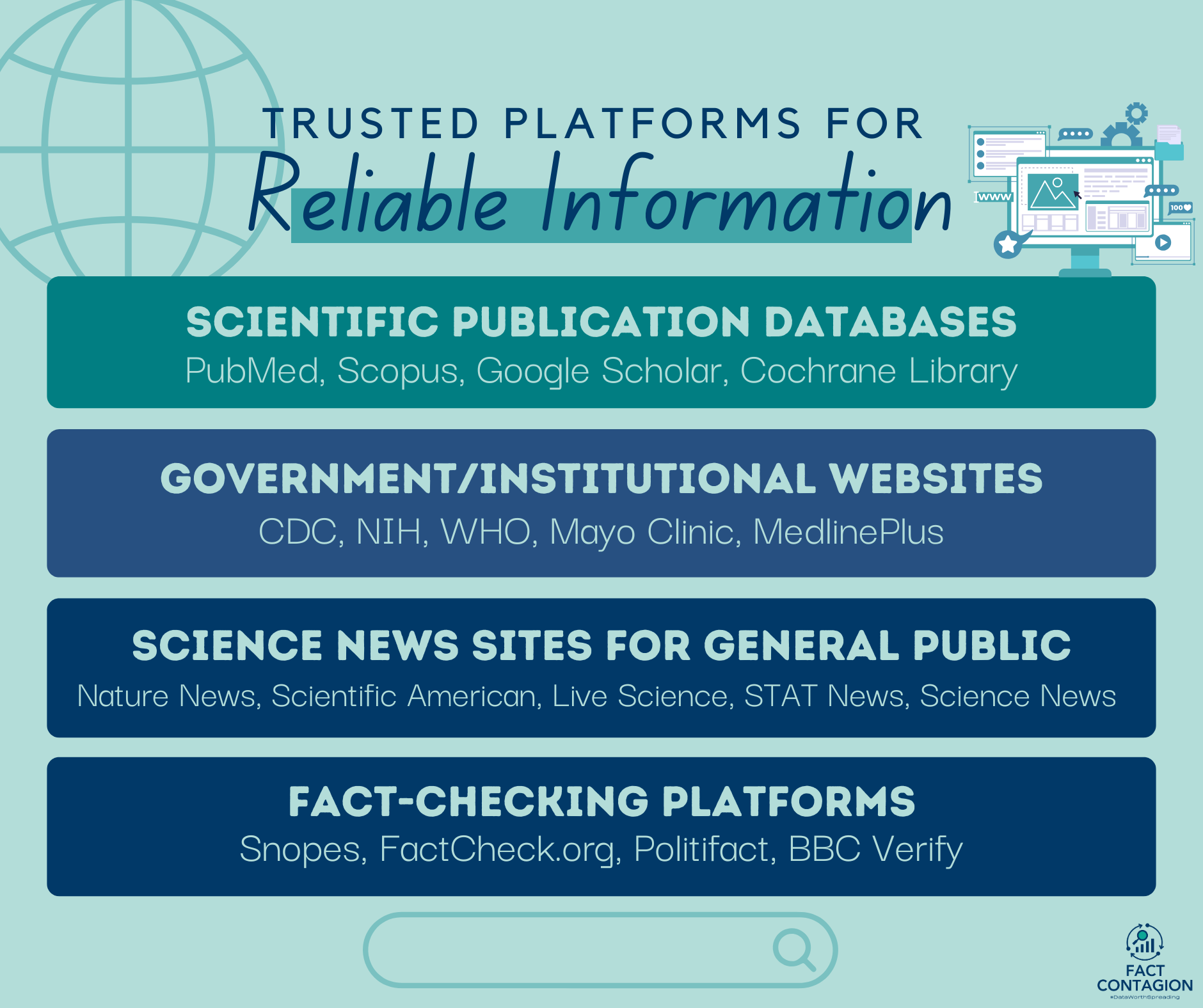

Trusted Platforms for Reliable Science Information

Scientific Publication Databases

- PubMed: Index of articles from peer-reviewed journals

- Scopus: Database of peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, and patents

- Google Scholar: Search engine for research articles, theses, books, and patents

- Cochrane Library: Database of systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Government/Institutional Websites

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Information on health guidelines, vaccines, and public health emergencies

- National Institutes of Health: Information on medical research and health topics

- World Health Organization: Global health topics, pandemic preparedness and response, international standards

- Mayo Clinic: General health advice and disease-specific resources

- MedlinePlus: Understandable medical information for the lay audience

Science News Sites for the General Public

- Nature News: Breaking science news and analysis from a leading research journal

- Scientific American: Accessible, evidence-based insights into scientific discoveries, innovations, and developments across a wide range of fields

- Live Science: Accessible coverage of current scientific discoveries, technological advancements, and natural phenomena

- STAT News: Delivers trusted journalism about health, medicine, and the life sciences

- Science News: Covers advances in science, medicine and technology for the general public

Fact-checking Platforms

- Snopes: Resource for fact-checking misinformation, debunking fake news, and researching urban legends

- FactCheck.org: Nonprofit website that provides original research on misinformation and hoaxes

- And their Science-focused page: SciCheck

- Politifact: Fact-checking website that rates the accuracy of claims by elected officials and others on its Truth-O-Meter

- BBC Verify: The UK-based media outlet fact-checks global misinformation

Common Misinformation Traps to Avoid

In addition to the general characteristics of unreliable sources noted above, there are additional red flags to exercise caution against. Below is a list of common misinformation traps that you should be prepared to recognize and avoid.

Over-the-top Narratives

- Sensationalized headlines or clickbait titles designed to provoke outrage or curiosity instead of accurate information

- Exaggerated claims, heavy emotional appeals, or conspiracy framing such as “The cure Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know!” or “The Government is hiding this medical breakthrough.”

- Pseudoscientific jargon that sounds scientific but is used without accurate definitions, evidence, or relevance; such as misused scientific terms, vague concepts (“toxins”, “DNA activation”), buzzwords ( “immunity-boosting”), over promised claims (“100% natural cure”, “scientifically proven miracle”)

- Missing nuance that oversimplifies complex issues into black-and-white thinking

Referencing Tricks

- Unsupported claims that lack citations/references to reputable studies, data, or experts

- Circular referencing to sources within the same dubious platform

Author/Platform has a Strong Bias or Hidden Agenda

- Conflicts of interest with industries, organizations, or agendas that have vested interests in the stated claims

- Political or commercial motivation that prioritizes agenda or profit over accuracy (e.g., far-leaning partisan websites, industry-sponsored content presented as unbiased journalism).

Poor Quality

- Unprofessional appearance with typos, poor grammar, or low-quality website or visuals

Misrepresentation of the Evidence

- Cherry-picked data that confirms the narrative while ignoring broader evidence

- Anecdotal evidence or personal testimonies in lieu of evidence-based research (eg, “I got the flu shot last year and still got sick, so vaccines don’t work” or “This herbal supplement cured my friend’s chronic pain.”)

- Reliance on non-reproducible conclusions that can’t be substantiated or confirmed by independent data or other studies

Inability to Accept Critique

- Refuses to acknowledge errors, issue corrections, or update conclusions when proven inaccurate

- Dismisses scientific consensus as conspiracy while promoting unverified claims

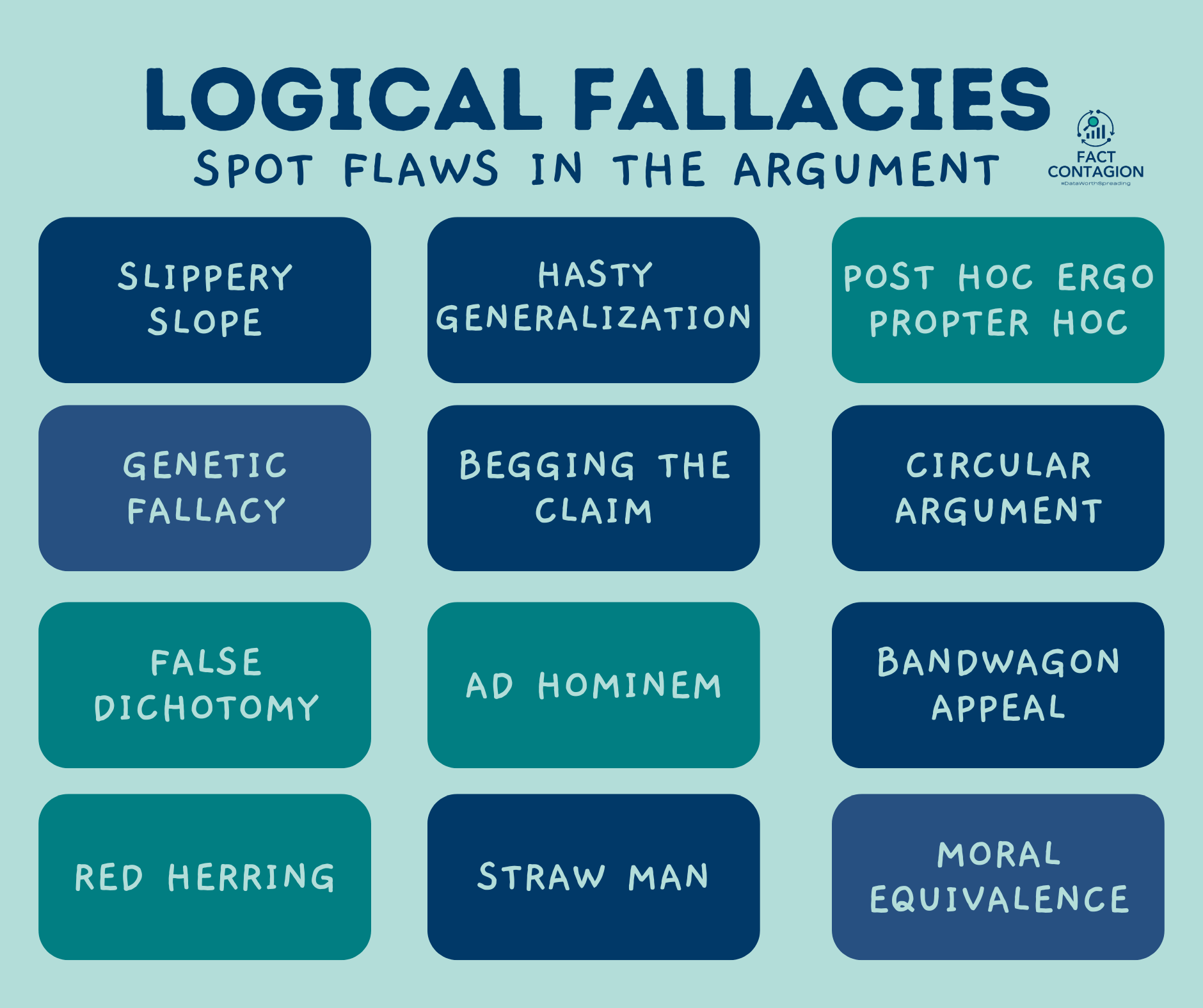

Faulty Logic: Spotting the Flaws in Arguments

Unreliable sources may also invoke logical fallacies to mislead, relying on flawed reasoning to create a false sense of credibility or to manipulate emotions.

Logical fallacies are essentially errors in reasoning that undermine the validity of an argument. Below are the common types, with examples provided by Purdue OWL):

- Slippery slope: If A happens, then eventually through a series of small steps, through B, C,..., X, Y, Z will happen too.

- “If we ban Hummers because they are bad for the environment eventually the government will ban all cars, so we should not ban Hummers.”

- Hasty generalization: Conclusion based on insufficient or biased evidence.

- “Even though it's only the first day, I can tell this is going to be a boring course.”

- Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Conclusion that assumes if 'A' occurred after 'B' then 'B' must have caused 'A.

- “I drank bottled water and now I am sick, so the water must have made me sick.”

- Genetic fallacy: The origins of a person, idea, institute, or theory determine its character, nature, or worth.

- “The Volkswagen Beetle is an evil car because it was originally designed by Hitler's army.”

- Begging the claim: The conclusion is validated within the claim.

- “Filthy and polluting coal should be banned.”

- Circular argument: Restates the argument rather than actually proving it.

- “George Bush is a good communicator because he speaks effectively.”

- False dichotomy (Either/or): Oversimplifies the argument by reducing it to only two sides or choices.

- “We can either stop using cars or destroy the earth.”

- Ad hominem: An attack on the character of a person rather than his/her opinions or arguments.

- “Green Peace's strategies aren't effective because they are all dirty, lazy hippies.”

- Bandwagon appeal: Presents what most people, or a group of people think, in order to persuade one to think the same way.

- “If you were a true American you would support the rights of people to choose whatever vehicle they want.”

- Red herring: Diversionary tactic that ignores key issues, often by avoiding opposing arguments rather than addressing them.

- “The level of mercury in seafood may be unsafe, but what will fishers do to support their families?”

- Straw man: Oversimplifies an opponent's viewpoint and then attacks that hollow argument.

- “People who don't support the proposed state minimum wage increase hate the poor.”

- Moral equivalence: Compares minor misdeeds with major atrocities, suggesting that both are equally immoral.

- “That parking attendant who gave me a ticket is as bad as Hitler.”

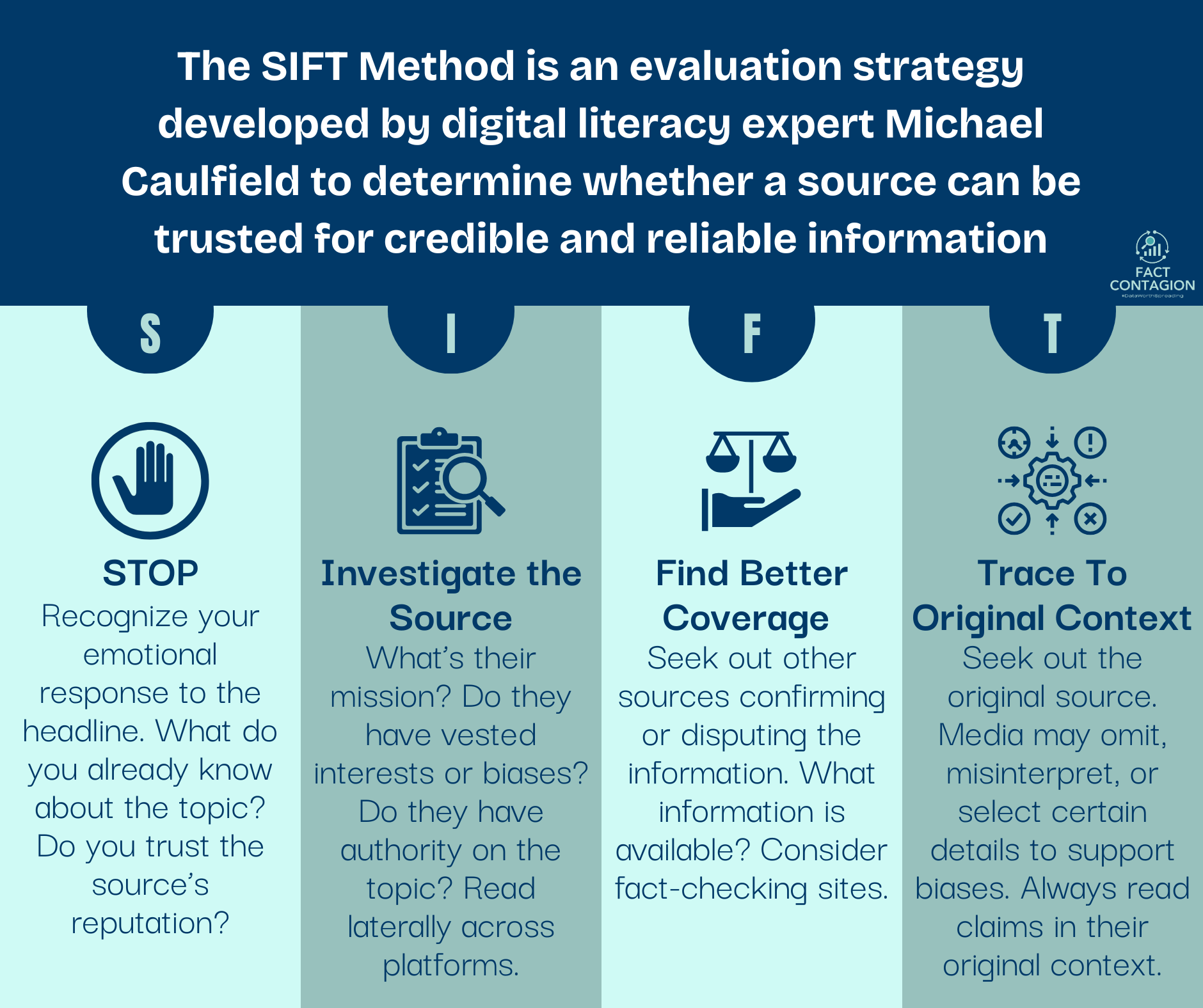

SIFT: A Strategy to Stay Informed and Critical

SIFT is an evaluation strategy developed by digital literacy expert Michael Caulfield to help you determine whether online media can be trusted for credible and reliable information.

UChicago Library nicely distilled the information from Caulfield’s book and updated content.

1- (S) Stop

Recognize your response to the headline. Headlines are often written to get clicks, and will do so by causing you to have a strong emotional response.

Before you share - or even read - an article, consider what you already know about the topic. Do you trust the website or the source? Do you know its reputation?

2- (I) Investigate the Source

Look up the author and publisher/platform. What can you find? What is their mission? Do they have vested interests? Could their assessment be biased? Do they have authority on the topic?

Read laterally across interconnected sites rather than deep-diving only into the site in question.

3- (F) Find Better Coverage

Seek out other sources corroborating the information or disputing it. What information is available on the topic? Focus on trusted sources.

Consider fact checking websites (suggested list above) that aim to increase public knowledge and understanding to confirm if claims are based on fact or if they are biased/not supported by evidence.

4- (T) Trace Back to Original Context

When an article references data, a study, a quote, or an expert, it is always good practice to try to locate the original source of information. Credible authors will do the first part for you and provide direct citations, references, and links. Click through the links to follow the information trail.

- Was the claim, quote, or media appropriately represented?

- Does the extracted information support the original claims?

- Is information being cherry-picked to support an agenda or a bias?

- Is information being taken out of context?

Media coverage may omit, misinterpret, or select certain details to support biased claims. Be sure to read the claims in their original context.

Empowering a Science-Savvy Community

My goal with this site is to help create a community where science literacy is our superpower.

Start slow. Question what you encounter on social media and in the news. Diversify your sources so you don't get stuck in an echo chamber. Soon, it will become second nature. You'll be better able to drown out the noise and spot misinformation traps.

So, the next time you come across a claim online, try applying the SIFT method. See if it holds up to your scrutiny. And share your findings with others! By spreading science literacy, we can build a more informed and resilient community.

Science literacy is about being curious yet grounded, open-minded yet discerning, and confident yet measured. Let’s work together to shape our perspectives and inform sound decision-making through data and evidence, not disinformation and mistrust.